One Man, One Nation: The Road to Independence

“He stretched his hand across the water.

He sent the love over the land and Sea.”

It was a turbulent era – wartime; it was one of the few periods in history when the colors of the Filipino flags were inverted with red on top and blue on the bottom. Yet, the rays on the flag– presenting the first eight provinces that revolted against Spanish Rule – were still illuminating the darkness. The Filipino independence was a struggle. The island nation was not only facing an intense domestic crisis but also enormous external threats during the World War Two. The survival of the nation was an unknown question.

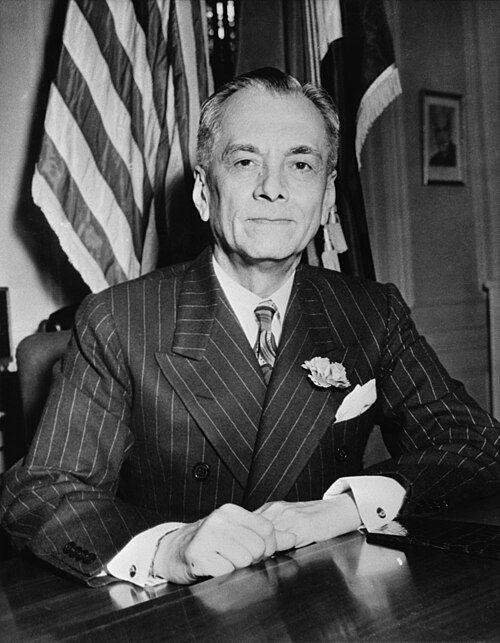

In the spring of 1942, demure but radiant in his familiar white suit, the exiled President Manuel Quezon slightly frowned; he slowly stumbled to the balcony on the second floor of the embassy building of the Philippines. Staring at the bustling Massachusetts avenue, the President was longing for a nation’s survival and, most importantly, independence. The bustling street dragged his thoughts back to years ago – the 1930 era, Manila.

It was the eve of the Holocaust. The President of the U.S. governed Commonwealth extended his arms across the sea and gave his heart from the distant shores, offering visas to Jewish refugees. In the era marked by antisemitism combined with the fear of the rising Nazi power, many great power states were refrained to offer the Jews a haven. However, an island nation chose to express its benevolence to the world, and it used its arms to embrace the Jewish refugees. Under Quezon’s unwavering commitment to broader human rights and dignity, the Open Doors Policy was enacted. Quezon’s unrelenting determination to secure visas from the U.S. Department of State eventually saved the lives of more than 1200 Jewish refugees.

The island nation undergoes a turbulent fate. The invaders were enticed by her beauty and splendor. They hence chose to enslave her. She yearned to be free like birds freely flying in the sky. The Japanese invasion of the Philippines forced Quezon to go into exile in 1942. It was a wartime necessity, maintaining a Philippine government-in-exile that was based in Washington D.C. Yet, the president could never know he stepped on a no-return journey.

Staring out of the Embassy’s window, on the same day back in years ago, the gentleman must have imagined an independent Tagalog Republic countless times deeply in his heart. For nearly two and half years, the Philippine government was entirely exiled in D.C., which was led by Quezon, his vice president Sergio Osmena, and other Cabinet members. These men actually lived here when they were exiled. Quezon and his family occupied a suite at the Omni Shoreham Hotel.

Throughout Quezon’s stays in Washington D.C., before and during the exile, he never stopped a single day fighting for the Filipino independence. As an appointed resident Commissioner to the U.S. Congress, Quezon fought tirelessly. In 1916, the passage of the Jones Act was an initial achievement of his efforts, which granted the nation greater autonomy and created a bicameral legislative chamber.

During the intense debate of the Jones Act, Quezon forcefully delivered his statement on the committee floor – “I am not a Democrat nor a Republican, nor even a Progressive,” but he is a Filipino. Asking his colleagues to imagine the struggles for a nation’s freedom, Quezon used the American revolution stories to highlight the sentiments back in his homeland.

More importantly, one of his most unwavering efforts includes his active lobbying actions to the U.S. Congress – the passage of the Tydings-Mcduffie Act in 1934. This legislation granted the Philippines full independence 10 years after the creation of the constitution and the establishment of a Commonwealth. He always wandered in the hallway of the Cannon Office Building of the U.S. Congress. He called the Capitol “at once the best university and the nicest playhouse in the world.”

Times in a foreign land were especially harsh – external political tensions combined with domestic struggles and racism. The gentleman never put down the restless dream of the Filipino freedom, the realization of an independent nation-state. However, what hit him down were not these struggles, but his health issues.

Quezon’s time was running out. He, himself, never has the chance to witness the nation to be free in person. In the fall of 1944, upstate New York, tuberculosis took away the life of the beloved man. Within two years, on July 4, 1946, the Republic of the Philippines was born. His body was placed in Arlington National Cemetery and brought back to the Philippines after the war.

Deeply in Quezon’s dream, there was always beautiful Tagalog republic where the Sampaguita jasmines are blooming on his childhood field of Baler, the birds are flying high in the sky, and men are happily living with peace and dignity.

Although the gentleman was born in an island nation, his vision extended beyond its shores. His benevolence and generosity knew no border.

Quezon should be happy up there.

As the Hebrew saying goes, “Whoever saves a life, saves the world entire.”

Cindy Sun-Esperanza

thefilamnews